|

||||||||||||||||||||||

Solomon Islands Culture

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Terry Marshall. A outboard canoe, Solomon Islands. |

Finally, the lorry skidded to a stop in a cloud of dust at a wharf on the eastern side of Malaita. It was the end of the road, and we were the only passengers left. A short wooden pier jutted into the ocean. A wiry, bare-chested man waited in the shade of a coconut tree chewing betel nut to pass the time. A canoe was moored to the wharf. It was bright blue fiberglass, with an orange triangular top over the bow that created a semi-dry space for luggage. An outboard engine hung off the back of the boat.

We were going to the Kwaio village of Ngarisaasuru. Since no phones or telegraph lines extended to that remote village, a week prior to our trip, we sent a public service radio message. Every day at 12:30 pm and 6:30 pm, Radio Happy Isles sends service messages. Locals in the Solomon Islands gather around small, battery-operated radios and listen to them religiously. Our message: "Disfalla message, hemme fo oloketa long Kwaio fo pikem up oloketa waetman long warf long tusde nex wik." (Translated, it means: "This is a service message for the people of the Kwaio to pick up some white men at the wharf on Tuesday, next week.") Service messages are one-way communications. We didn't get a response confirming they would send someone. At nine years old, I was completely confident in the system; I didn't know any other way. Luckily, someone had heard the message, and sent a canoe. If not, we would have been stranded on an empty wharf at the edge of the jungle, far from any population center.

"Allo, Mista Marshall, an Missus, an pikinini blong you." ("Hello, Mister Marshall, and Missus, and your child.") The canoe driver greeted us as the lorry driver tossed our bags from the back of the lorry. The canoeist caught them and carried them to the boat. He wore a faded pair of khaki shorts. His well defined muscles were tight under his glistening black skin. His tight afro had reddish highlights where the sun had bleached it.

My dad helped the driver stuff our bags into large rubber sacks and jam them into the space in the bow. He repacked it several times trying to keep it out of the water sloshing in the bottom of the boat. On the dock, mom instructed, "When we get there, Leslie, the village big men will want to shake your hand."

Ultimate Language Secrets

You've learned about Walkabout language learning. Want more ideas about how to learn languages faster and easier? Owen Lee is an expert language learner; he speaks half a dozen languages. He gives you tons of language learning ideas in Ultimate Language Secrets.

Leslie, at Your Language Guide has read this book and she thinks that it has fantastic ideas about language learning. Plus, we love the free Beyond Languages book that he includes. Read the full review.

I groaned. I hated the protracted ceremonies that we went through when we visited remote villages. On one visit, I remembered a half day under a hot sun touring the island on a slow moving tractor as we laid thick licorice-like sticks of tobacco on sacred sites. On a different visit, we sat for hours cross legged on straw mats drinking the juice of green coconuts. It tastes like stomach acid mixed with Sprite. I couldn't stand the stuff, but couldn't refuse it without being rude. Now she was prepping me for another boring greeting ceremony. "I don't want to shake people's hands."

"Youve got to. Theyll think youre rude," mom scolded.

"Leslie, you need to shake anyone's hand who offers it to you." Dad settled it. I wrinkled up my face at the thought, but I didn't say any more.

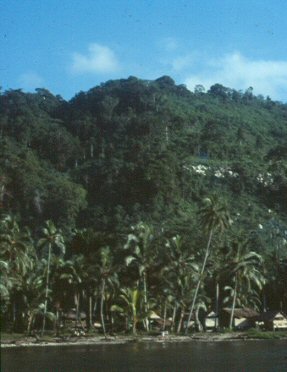

I donned my U-shaped life preserver: two puffy orange tubes tied to my chest and a floppy pillow behind my head. I hated it; the seam cut into the back of my neck. Plastic planks spanned the width of the canoe and provided seats for the passengers. Strong black hands lifted me into the boat, and I could smell the man's scent brought out by the roasting effect of the sun. My short legs dangled. I had nothing to lean against. The sea spray soaked my shorts and t-shirt, and the wind quickly chilled me. Thirty minutes with the boat slapping the water seemed like forever, but at last, the Kwaio's mountain rose out of the gray-black sea.

|

|

Terry Marshall. Mountain home of the Kwaio, Solomon Islands. |

As Peace Corps country co-directors, my parents were the highest-ranking US government representatives in the Solomon Islands. With the US ambassador stationed a thousand miles away in Fiji, they filled the day-to-day role of US liaison. Locals in the Solomon Islands respected them not only because of their position, but also because of their cultural sensitivity and their efforts to help develop the Solomon Islands. Because of their rank, many village elders and a few matriarchs gathered on the shore to greet us when we arrived.

In an instant, my hand was engulfed in hand after hand: wrinkly hands, clammy hands, dry hands, hard hands, gripping hands, limp hands , hands with long fingernailsyellow and dirtyhands with work engraved into the fingerprints. They were all Melanesian hands: black on the outsides, peachy gray on the insides. I put on a brave face so I wouldn't shame my parents, but touching all those people made me want to shiver in disgust; it was too intimate for me.

Finally, the greetings ended, and we continued our journey to the Kwaio. I danced around at the thought of getting away from the tedious greetings. "Let's go. Let's go." I scampered up and down the path from the beach to the edge of the jungle while several young men slung our things, plus a 50-kilo bag of rice across their backs. My parents brought the rice as a gift to our Kwaio hosts.

|

|

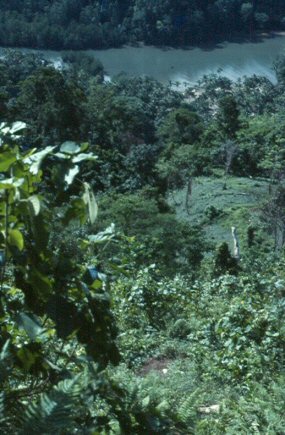

Terry Marshall. Jungle path leading to the Kwaio, Solomon Islands. |

The Kwaio village sits atop a mountain that juts steeply out of the Pacific. A narrow dirt footpath crossed the pebbly beach and disappeared into the jungle shade. It wasted no time with switchbacks, choosing instead to climb straight up. Roots occasionally crossed its path, acting alternately as handholds and footsteps. Trees, some thick, but many only five inches in diameter rose up all around us; the path jogged around the largest ones. The dirt felt hard and cool underfoot. In spots, slick mud made difficult footholds. My toes gripped the path; and my hands grasped roots, vines, or nearby trees. I loved that climb.

My parents worried that I would tire out during the climb; a needless concern -- I skipped up the mountain, keeping pace with our guides. I was in my element. The jungle provided a cool canopy, and I loved clambering over rough spots and grabbing on to vines for support. It was a three-hour hike for us, even though a Kwaio walking at a "normal" pace could make it in forty-five minutes.

|

|

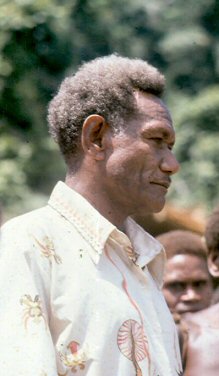

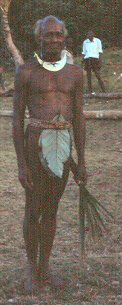

Terry Marshall. Jonathan Fifi'i, member of Parliment, Solomon Islands. |

When we arrived, our guides took us to a hut situated away from the village. A white man came out. "Terry, good to see you again." My dad had come here almost a year earlier to make arrangements for volunteers to be assigned to live among the Kwaio. Later, he told me about that first visit where he sat in an all day and into the night meeting with the village bigmen. Everything was done by consensus, so the discussion went on and on. He talked in Pidgin while Jonathan Fifi'i, a Kwaio born Solomon Islands Member of Parliament translated into Kwaio. At the end of the discussions, the village elders said, "We don't understand what you are talking about, and if you were English, we would not trust you. But you are American; we trust Americans. We will accept your Pisco volunteers." After they sent him away, they continued meeting into the wee hours of the morning. The topic: whether or not their village should pay their required taxes to the Solomon Islands government.

After introductions, I puzzled over why the couple lived away from the village, and as we walked away, I asked, "Are they the volunteers who live with the Kwaio?"

"No," Mom said.

"They're missionaries?" If they weren't volunteers, what else could they be?

Mom said, "No, Roger is an anthropologist." I searched my brain, "anthropologist;" I didn't know that word. Oh, well, I figured, an "anthropologist" must be like a missionary, a white man who lives in the bush. Everyone was preoccupied with introductions and it wasn't a good time to ask questions. I remained silent.

|

|

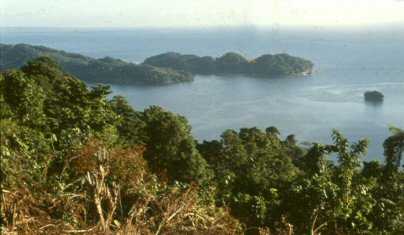

Terry Marshall. Ocean view from Ngarisaasuru, Solomon Islands. |

Years later, I learned that Roger Keesing was a famous anthropologist who wrote dozens of books about anthropology and the Kwaio. He was documenting Kwaio culture, and recording their unwritten traditional language. He'd been living part-time in the village for almost ten years. He initiated the request to the Peace Corps for two volunteers to help build the Kwaio Cultural Centre.

The Kwaio, an ethnic group that lives on the eastern side of Malatia Island have a history as fierce warriors. In the late 1920s, Kwaio warriors killed fifteen government officials, including the District Commissioner, an Australian, William Bell, in an act of defiance against paying taxes. Vengeance by the colonial government was swift and severe. About 60 Kwaio were killed and 200 imprisoned. More significantly to the Kwaio, their holy sites were systematically desecrated, an act which for them would bring about the wrath of their ancestors who punish their own descendants through natural calamities.

|

|

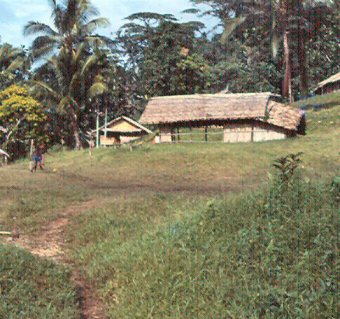

Terry Marshall. Kwaio cultural centre, Solomon Islands. |

In the intervening fifty years, the Kwaio had mostly given up their warlike ways, although they still rankled over paying taxes. Some converted to Christianity--out of fear of supernatural vengeance from their ancestors--and moved away from the remote villages, but a determined portion of them held tightly to their traditional ancestral worship religion. They remained aloof from other Solomon Islands people, descending the mountain only to trade on market day. Malaitans distained their pagan lifestyle and gave them a wide berth (the majority, about 97%, of people in the Solomon Islands are Christian). Even though I didn't know about the Bell Massacre, and even though the greetings were friendly, I had sensed an undercurrent of isolationism earlier that day on the beach. The Kwaio had resisted contact with the outside world. Their remote location and strong ethnic traditions caused them to shun modern influences. There was no electricity, no telephones, no stores, no roads, cars, or bicycles in this village. They kept their history and genealogies alive by oral tradition.

Next, we went to David and Kate Akin?s house, where we would stay during our visit. David and Kate were the Peace Corps volunteers assigned to the Kwaio to help establish the new Cultural Centre and a school. In spite of powerful traditions, Kwaio culture was slowly eroding. The youth were not learning the crafts and traditions of their elders; some skills had already been lost. The cultural centre sought to preserve Kwaio traditions, craft making, religious practices, and oral genealogies by using Kwaio elders to instruct young boys and girls in the ancient ways. The school would teach elementary subjects including math and reading and writing in the Kwaio language, this would allow them to document their own history and traditions. We had come to Kwaio-land to celebrate the opening of the Cultural Centre.

|

|

Terry Marshall. Typical home Ngarisaasuru, Solomon Islands. |

David and Kates house was built of palm leaves and stood on stilts like the rest of the houses in the village. "This is our house. Let me give you the grand tour," David said. He motioned to my parents, "After you." We ascended a primitive ladder into the house.

"Welcome to our humble Kwaio abode," he said as we stepped through the open doorway--there was no door -- into the hut. "This is the living room, kitchen, dining room," he said. It was smaller than our living room back in Honiara, perhaps ten feet square. One corner was set aside as the "kitchen." A window, which was a cut-out in the leaf no glass and no screen looked over the clearing that made up the center of the village.

"And this is our bedroom," he waved toward the front right corner.

"Kwaio dont use beds, so neither do we; we sleep on the floor."

"Wow. On the floor?" My dad couldnt believe it -- the floor was split betel nut tree trunks, each about an inch in diameter, laid side by side, rounded side up--an uneven, and unforgiving surface. Needless to say, we slept on the floor during our stay too. I tossed and turned and woke up many times during the night.

After our tour, Kate offered, "Its a long trip from Honiara to the top of this mountain. Want to take a shower bush-style?"

|

|

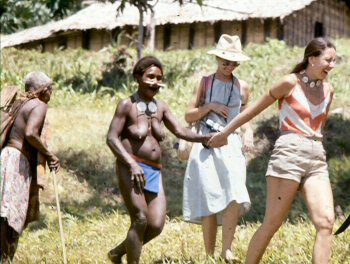

Terry Marshall. Kwaio woman with bone jewelry and Shelly Keesing, Solomon Islands. |

She didn't have to ask twice. We grabbed our towels, shampoo, and soap, slipped our swim suits on under our clothes and trekked to the nearby river. We met several villagers on our way . . . some of them mostly naked. Kate explained, "Married Kwaio women here wear only that six-inch square of cobalt-blue fabric covering their privates. Unmarried women wear nothing. When we get to the river, well have to split up. Terry, youll go with the men upstream from us. Ann and Leslie, Ill take you to the area were the women bathe. Women bathe downstream from men, because they are unclean . . . wouldnt want to pollute the men, you know."

|

|

Terry Marshall. Kwaio elder, Solomon Islands. |

I noticed that the men wore only bark loincloths. Maintaining the tradition to go naked is perhaps another factor that kept them isolated from other Malaitans. Most Solomon Islanders wore Western clothing--shorts for men, and dresses or skirts for women (though not always with a top). The bare-breasted women were normal in the Solomons. Only the young women with their firm breasts shocked me; weren't they embarrassed by their pert su-sus, I wondered. I was embarrassed for them. Their juvenile su-sus stood out in stark contrast to those of the married women, whose breasts looked like a pair balls in brown socks sagging half-way to their navels.

At the river, dad disappeared up a small path and out of sight. Mom and I stripped to our swim suits and splashed into the knee high water. A waterfall tumbled over some rocks creating an icy shower. I splashed under it just long enough to swish away the dust and dashed back to the bank to wrap up, teeth chattering, in my towel. I didn't even take time to lather up because the water was so cold.

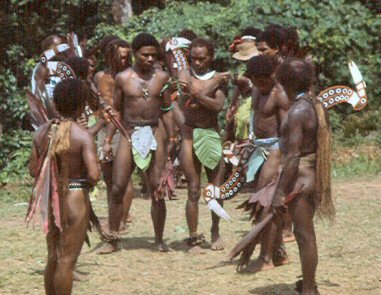

During the celebration, the villagers treated us to mock battles and traditional dances. A group of the village bigmen danced with only a large leaf to cover themselves. They wore menacing war masks and enacted a fierce battle. I was frightened by the angry pounding of their feet and the impassioned dance. Some of the men's leaves got sliced of during the battle. Their naked bodies added to my shock. Although I was accustomed to bare-breasted women, I'd never seen public male nudity.

|

|

Terry Marshall. Kwaio men prepare for traditional dance, Solomon Islands. |

Then came the big day: the feast. Everyone was up before dawn, and the villagers spent most of the day prepping for the feast. The men had slaughtered ten pigs, some time before we arrived, and had them slow cooking in fire-pits. The women slaved all day bent over cooking fires in cook houses behind each village house. Thin gray smoke from cooking fires painted blurry lines in the air. Children screamed and laughed with their special feast-day treat: balloons made from blown up pig bladders. I was horrified -- I couldnt imagine sticking your mouth on a pee bag to blow it up.

The day wore on. Then, as if by magic, an unspoken cry went out: the feast was ready. People swarmed in. My parents and I raced down the hill to the . . . to the what? This was the banquet table? They had laid out 100-foot-long row of banana leaves and palm fronds on the ground. In the center of the "table," in the seams of banana leaves, piles of food stretched as far as I could see in either direction: fists-full of white rice, fish, pig, taro, plantains. But no utensils . . . no forks or spoons, no knives. And no chairs or cushions or soft places to sit. We plopped down on the hard dirt. We ate with our fingers. If you wanted something several piles down, you leaned over and grabbed some. Everyone shared with the people closest to them: strangers, friends, and family. I was both shocked and excited. Excited at being given permission to eat with my hands, but horrified at the idea of eating without washing our hands. (I was concerned about germs.) Plus, I was shy about sharing with people that I didnt know. But it was good!

The Whole World Guide

Love the ideas and language learning tips here in our website?

Want to learn more about the Walkabout method? Buy your own copy of

The Whole World Guide to Language Learning:

How to live and learn any foreign language.

This book is chock full of ideas on how to use Walkabout language learning. It has sample lesson plans as well as language learning drills and practice tips. Order your copy today.

Meat and vegetables and fish stewed in their own juices. The rice was sticky and easy to eat with my fingers. I avoided the taro, slices of gray, dry root crop because it looked like potatoes. Potatoes made me gag. The plantains were boiled. My parents handed me some fish, a white flaky fish seasoned with flavors that I couldn't discern. It was delicious. I looked in vain, but there was no more of that fish within my reach, and I couldn't imagine asking a stranger to, "Pass me some more of that white fish over there." Fresh fruit, its sweet juice dribbling down our chins. Thats a feast!

As the food disappeared, the feast drew to a close, but celebrations continued into the night. Singing, whoops, and hollers pierced the night as I fought to sleep on the corrugated betel nut bed.

The next day, we packed up and trekked down the mountain, back to the waiting canoe, to the wharf, by truck over the mountain to Auki, and back to Honiara in that skitterish little plane.

I was only a kid then, but I knew that not only had I partaken of a rich cultural tradition, I had experienced a moment that few white people see. I had shared a special moment with a people unknown by 99.9999 percent of the world. In retrospect, I realize that living in the Solomon Islands was an exotic experience, but visiting the Kwaio made daily life in Honiara seem commonplace. Now, thirty years later, I wonder what the Kwaio are up to, but without electricity, it's not like I can drop them an email or check out their website on the internet. I feel lucky to have visited them when I did.

Return from "Solomon Islands" to Culture Stories

Return to Your Language Guide home

Multicultural Literature

Like this story about the Solomon Islands? Check out the latest additions to our multicultural literature section: Multicultural Stories.This section offers both fictional and non-fictional stories and essays set in regions around the world. You can read them on line for FREE.

When Leslie was a child, her family lived in the Solomon Islands. While there, they visited many remote and indigenous people of the Solomon Islands.

The Whole World Guide

Love the ideas and language learning tips here in our website? Want to learn more about the Walkabout method? Buy your own copy of The Whole World Guide to Language Learning: How to live and learn any foreign language.

This book is chock full of ideas on how to use Walkabout language learning. It has sample lesson plans as well as language learning drills and practice tips. Order your copy today.

Cultural Diversity

Links

Moving overseas? Use these links to learn more about the country you are visiting.

General Culture Info

Culture Corner

Culture Shock

Define Culture

Language and Culture blog

Africa

Americas

Canada

Because of my grandfather

Cuba

A flight into the past

Intrique sizzles in the air

Cuban Jews in Havana

Holocaust Tributes in Cuba

Cuba Classic Cars

Cuban People

Ernesto Che Guevara

Fancy Cuban Resort

Cuban Life

After 50 Plus years of Castros

Cuban Embargo

Experience Cuban Culture

Ecuador

Medical emergency

Mexico

Peru

Peru Blog

On the trail to Machu Picchu

Peru Things to Do List

Drill some Spanish into my brain

Free Spanish Lessons

Thirty Hours to Cusco

Beginning Life in Cuzco

It hurts . . . here and here

I Need a Doctor

Altitude Sickness!?

Learn Spanish in a Taxi

Chela's Story

Peruvian Inca Architecture

New Seven Wonders of the World

Mistico Machu Picchu

Machu Picchu Top Life Experience

Spanish tutorial: Meet my tandem

Learn Spanish Grammar in Peru

Typical Language Learning Day

Real Life Practice

High finance in changing money

Mario Vargas Llosa Teaches

The Road to Moray

Ultimate Fighting Championship

Images of Peru Housing

Peru History: Choqequirau

Ecotourism Travel in Lake Titicaca

Spare Me the Nescafe

Colca, Condors, and Guides

Contaminated Bottled Water

Pictures of Peru

United States

Add another country

Asia and the Pacific

China

India

Introduction to India blog

India's Culture: Welcome to Delhi

What Happens When a Cow Dies?

More Cow Tales

Good Clean Bathroom Humor

Paint a Picture of Road Traffic Safety in India

Am I Talking to ... Myself?

No water? India's Dilemma

Indian Clothing Here and There

Singing Songs and Swimming Swamp

Don't Spoil Your Car

Explore the Taj Mahal

Poverty in India: A little TV tonight?

Sweet Shops

Japan

Solomon Islands

Brittish v American English

Big Feast in the Kwaio

Throw those (under)pants out

Rediscovering the Wheel

Add another country

Europe

Bulgaria

Getting the Meaning Right

France

Greece

Italy

Got a hit of Air

Italian Culture

Sweden

Swedish Fika

Embarrassing Bed Sheets

Santa Lucia

Ukraine

Prisoners of the Past

Add another country

Middle East

Other

Study Abroad

Typical study abroad day

Moving Overseas

Add another topic

Then why not use the button below, to add us to your favorite bookmarking service?

Copyright© 2007-2016 YourLanguageGuide.com

All rights reserved.

Return to top

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.