The Search for Ernesto Che Guevara

Note: Ernesto Che Guevara is part of a travel blog that we wrote during a humanitarian mission to Cuba. We are convinced that language opens a gateway to understanding culture. These pages focus on the culture of a country that has been relatively isolated for a half century. Our visit offered an opportunity to explore a place that few of our countrymen have seen. While we were there, we practiced Walkabout Language Learning to improve our Spanish and spent time with Cubans through a Jewish medical mission and informal encounters in Havana. See the list of "More Cuba Stories" on this page to explore how culture and language intertwine.

"We want to be like Che -- Fidel"

"We want to be like Che -- Fidel"I've waited 50 years to meet Ernesto Che Guevara. Now, my heart races as we taxi in at José Martí International Airport in Havana.

My friends tell me I'm delusional: Che's dead, they insist, assassinated in Bolivia, October 9, 1967. Their proof: Steven Sodenbergh's 2008 movie, Che, that 4 1/2-hour-long biopic.The movie looks pretty persuasive, but, after all, it's a movie, not live footage. What if Che -- like Elvis -- isn't dead after all?

Before this trip I dug out my yellowed copy of the June 27, 1968 Ramparts magazine: Che's diary in full, the first English translation. His last entry is October 7, 1967. The Bolivian army has him and his 16 companions surrounded. It looks bleak for Ernesto Che Guevara, but he's hopeful. And he's still alive.

Quotes on Cuba's National Icon

Che and Fidel

Che and Fidel"Many will call me an adventurer -- and that I am, only one of a different sort: one of those who risks his skin to prove his platitudes." -- Ernesto Che Guevara

"I am not a liberator. They do not exist. The People liberate themselves." -- Ernesto Che Guevara

"A man of profound ideals, a man in whose mind stirred the dream of struggle in other parts of the continent and who was, nonetheless, so altruistic, so disinterested, so willing to do the most difficult things, to constantly risk his life . . . Che was an incomparable leader" -- Fidel Castro

We disembark. I'm dying to see this city. I do my best to cope with the airport drill -- immigration, baggage, customs -- then push through the crowd amassed at the exit passage. My first glimpse of Havana: a taxi-line of pre-'60s Chevys . . . yes!

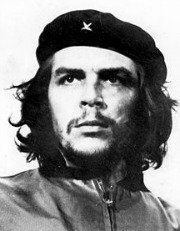

Then, looming beyond the parking lot, a billboard with that famous image: Ernesto Che Guevara. Black beret with its single star, head high, a guerrilla's beard and scruffy hair, confident stare into the future. The billboard assures me he's alive: "We see you every day. . . Che Comandante, amigo," it says in Spanish. (We love the mini Spanish lessons we get from local signs. Get ideas about how to extended your language learning.)

Che's portrait is all over Cuba: on billboards, banners, posters, books, t-shirts, even an eight-story-high iron sculpture on a high rise overlooking Havana's massive Plaza de la Revolución.

Apparently he is Cuba's Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, and Teddy Roosevelt all rolled into one. Occasionally, we see a billboard that mentions Fidel Castro -- but they don't lionize Fidel; they quote Fidel honoring Che.

Though I'm in Cuba as part of a group of seven Americans bringing medical supplies to synagogue-sponsored clinics, we do have time for sightseeing.

So, four days into our visit, we're off to "Che Central" -- Santa Clara, a city of 210,000 some 170 miles east of Havana. Here, on New Year's Eve, 1958, Che's guerilla forces routed dictator Fulgencio Batista's army en route to final victory in Havana on January 1, 1959.

Ernesto Che Guevara's final resting place.

Ernesto Che Guevara's final resting place.Ann Marshall

Ernesto Che Guevara on High . . . in Bronze

You can't miss Santa Clara's Monumento Ernesto Che Guevara.

It's massive . . . Soviet-style massive: a sculptured city block anchored by a huge plinth hosting a bas-relief of Che's guerilla life and sayings, and a 22-foot-high bronze statue of Che in full stride, rifle in hand. (By comparison, the marble sculpture in Lincoln's Monument is 19 feet tall, though Lincoln is sitting, not striding into battle.)

We mount the steps of the plinth, study the bas-relief diorama, take a crack at translating his quotes, then plop down and survey the complex. We need a rest; it's that big.

No question, Ernesto Che Guevara remains the Cuban national hero, even though he was an Argentine.

But there's a surprise here, too: at the back of the plinth, we peer over the edge . . . and see a young couple emerge from the rear of the monument. We work our way to the ground, then hike around to the back. A set of rear doors lead into a small chamber. To the left is a mausoleum; Che's ashes are entombed here. To the right is a small museum; Che's life is honored here.

Entrance is free. A sign warns: no photos. An attendant stands ready to enforce it.

Che's Ashes at Rest

Che, Cuban hero.

Che, Cuban hero.Wikipedia

Inside the mausoleum, we pause so our eyes can adjust. It's an artfully designed cave, dimly lit. Its low, arched ceiling and right-side wall are a 3-D mosaic of jutting dark, polished wooden blocks. They cast the mausoleum in eerie shadows.

More Cuba Stories

The granite wall to the left is inset with niches for Che and the 38 revolutionaries killed in his last battles in Bolivia; 17, including Che's, hold the men's ashes. Each is identified by his first name; no last names needed. The room's light comes from a small five-point star inset in the ceiling, and an eternal flame that burns at the far end of the room. We and a handful of other visitors silently shuffle through; even whispers seem inappropriate.

I'm reminded of Ho Chi Minh's mausoleum in Hanoi. Communist nation. National hero. Sacred place. But Ho Chi Minh's body lies in state, guarded by a phalanx of menacing armed soldiers. They enforce reverence. Here, decorum speaks for itself; the attendant merely looks on . . . and she has no gun.

A Museum of Che's Life

Next door, a small museum celebrates Ernesto Che Guevara as a man, as revolutionary, as government official: boyhood photos; a grade school report card; his medical license; photos from album-size to huge wall blow-ups -- Che in battle, in conversation, at the United Nations; relics -- his pistol, his guerilla uniform, including that famous black beret with the five-pointed star; his book on guerilla warfare; bank notes printed with his signature as Minister of Finance in Fidel's government.

The exhibit extolls Che's campaigns for health care, literacy, land reform; his work as Minister of Finance, Minister of Industries, as an international diplomat, as a writer and theorist, as the man in charge of training Cuba's post-Batista army.

Ernesto Che Guevara, Cuban hero: A monument to match the reputation.

Ernesto Che Guevara, Cuban hero: A monument to match the reputation.Ann Marshall

It doesn't explore Che's role in the post-war tribunals and executions of Batista officials, or in bringing Soviet missiles to the island, or the legacy of his economic reforms that left the nation in poverty, or his unsuccessful efforts to bring revolutions to the Congo and Bolivia. Che stamped an indelible mark on the world . . . but he wasn't a saint; this museum doesn't say that.

On the way out, I look for the gift shop. A souvenir would be nice: a book, The Motorcycle Diaries, perhaps; a facsimile page of Che's diary; a reprint of Alberto Korda's famous portrait of Che, Guerrillero Heroico; or even a poster. Anything that says "Made in Cuba" -- physical proof I've been here. Not a t-shirt or beret, though; they've got tons of those in the marketplace.

But guess what? The museum has no gift shop, nothing for sale.

This place honors Ernesto Che Guevara and keeps his memory alive.

The museum, like Che and Fidel Castro's Cuba, wants nothing to do with capitalism.

Interestingly enough, under Raul Castro, Cuba's forbiddance of all things capitalistic seems to be changing -- gradually.

Che: His Life in Brief

1928 June 14: born in Rosario, Argentina.

1953: Completed medical degree in Buenos Aires. Traveled through Venezuela, Peru, Ecuador, Panama, Costa Rica and Guatemala.

1954 June: failed an attempt to overthrow the Guatemalan government. Fled to Mexico, where he met Fidel Castro and other Cuban exiles.

1956 December: invaded Cuba with Castro and his insurgents. Named guerilla commander in June 1957.

1958 December 29: Che's troops captured Santa Clara. Marched into Havana January 1, joining Castro's other forces.

1959 October: named head of the Industry Department in the Agrarian Reform's National Institute, then president of the National Bank.

1960: published his manual on guerilla warfare, Guerra de Guerrillas.

1963: spoke to United Nations' Assembly; travelled to Mali, Guinea, Ghana, and Tanzania.

1964: traveled to China, Paris, Algeria, Moscow, Mali.

1965: traveled to the Congo, Guinea, Ghana, Dahomey, Algiers, Paris, Tanzania , Congo, China.

1965: travelled through Uruguay, Brazil, Paraguay, Argentina, and Bolivia. In April, gave up all his official positions and his Cuban nationality. Secretly returned to the Congo.

1966: Fled the Congo, traveled through Uruguay, Brazil, Paraguay, Argentina and Bolivia. Began his Bolivian guerrilla campaign in November.

1966-7: Recorded his attempt to overthrow Bolivian government in his diary. Last entry: October 7, 1967.

October 9: executed by Bolivian Army troops.

Previous: Warm encounters with Cuban people

Next: Living the good life in all-inclusive Cuba

Terry Marshall is a language and travel enthusiast and a writer who created Walkabout Language Learning. Follow my blog as I replace decades of old memories with new observations about the culture and the place in a series of posts on our humanitarian mission to Cuba. If you have visited Cuba, I encourage you to share your experiences or leave a Facebook comment below. If you have questions about my trip, please ask. To read more of my writing, click here.

Stay in Touch with Language Lore ezine

Want to stay in touch? Subscribe to Language Lore, our internet language learning email newsletter. This free ezine facilitates your language learning journey. See our back issues here.

Go to your email now to confirmation your subscription. If you don't see an email within an hour (check your junk mail folder too), please contact us. We respect your privacy and never sell or rent our subscriber lists. If you want to get off this list later, one click unsubscribes you.

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.