American Model

I posed as a model by accident, I swear it. I told Mother it is God’s will. “Yes, it must be God’s will,” she sighed. She is a good Catholic, and had no other answer.

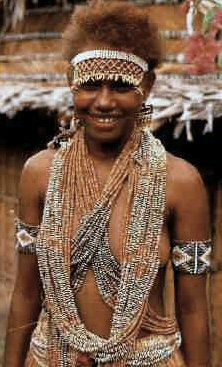

| From Solomons#9 (1992), the magazine of Solomon Airlines. Esme is a fictional character. This young lady is not Esme -- nor is this story about her. We show her here to illustrate the attire Esme describes in American Model. |

But I confess: that accident was something more also.

My cousin-sister and I were acting crazy in the window of Guadalcanal Arts and Artifacts, when the American photographer passed by on Mendana Avenue. He was the accident, that Kincaid.

Jully, my cousin-sister, manages Guadalcanal Arts. I come to stori with her, to make her days not boring. I am at loose ends. At the new year I begin graduate school in Canberra. Four months! I bide my time. I read, draw, stori with Jully. I taught briefly, Pijin language to expatriates, but that programme ended. Mother wishes me to marry. “Esme, you are twenty-four!” she wails. I am not ready, nor is there anyone. We have lived here in the capital city, in Honiara, long enough that Father does not insist to arrange a marriage.

Today Jully tells me, “Look, Esme, Mr. Cremmins bought this bride’s headband, an antique from your mother’s village.” Mr. Cremmins is Jully’s bossman, a waetman from Australia. He lives in Solomon Islands sixteen years now.

< 2 >

The headband is old, a century, but flawless. It is more than four fingers high, of tiny shell monies, the rare red ones, ground by a woman’s hand flat and round as collar buttons, then strung on a cord woven of coconut fibre and a virgin's hair. One hundred polished porpoise teeth dangle as even as pearls from the bottom hem. I cannot resist; I must wear it. “May I?”

Learn Exactly What you Need When you Need It

You know what language skills you want, Walkabout Language Learning Action Guide shows you step by step how to create your own language learning program. The Action Guide shows you how to put it all into practice.

- You control the vocabulary you learn.

- You practice the skills you need.

- You decide how much time to spend.

- Tailor your study to meet your needs.

- Learn at your own speed—whether that is fast or slow.

- You decide how to use this guide.

- You assess your progress.

- You decide when you’ve reached your level of mastery.

- You get an in your ear guide to direct your study.

- Follow step by step instructions to create your own language lesson.

You learn exactly what you need when you need it, not a bunch of verb conjugations that will trip you up every time you open your mouth.

The Walkabout Language Learning Action Guide contains the key to unlocking your language learning dreams.

“I set it aside for you,” Jully says.

I model before the mirror. This bridal headband tugs me like an insistent child, Come, Esme, come! Our village calls, tradition calls! Were I to return to my ancestral village, this headband would be one sparkle in a glittering array. I would parade through the village. All would bow in praise. My wedding would spawn a week of feast-days. My uncle is chief.

In the mirror, I seem a street urchin playing dress-up. A bride's headband looks foolish with a T-shirt. Jully thinks so also. She says, “Like high heels on a market vendor, eh?”

Jully’s eyes dare me, and I accept her challenge. She rushes off, returns with a bandolier of red and white shell monies draped on her arm like a flowing robe, a Lau wedding sash. She has also a betrothal apron of maku, the pounded bark-cloth made by ancient Lau people.

< 3 >

I was twelve when we fled Sulufoa to Honiara. Village life swims into memory: plant, dig, haul sweet potato; carry water; build a pit-fire, cook; tend children; so much work–but also hours free. Pre-menses, we girls ran naked. I was a butterfly tasting each bush, drawing nectar from every blossom, a barefoot skinny girl, fast as wind. Mother wore a tattered skirt, nothing more. In Honiara, we are moderns. We laugh at village women who go bare-breasted as if today were fifty years past.

At Teachers College, I formed Kakamora, a club to revive traditional dance. We crafted our outfits to be authentic–each shell necklace, headband, bark skirt, ankle rattle. But we were city girls, we refused to dance bare-breasted, not from shame–for a woman’s susus are a gift from God–but to set ourselves above village girls, uneducated girls. We wore Bali bras beneath our shell necklaces, cotton panties under native skirts. The boys cat-called and laughed. They shamed us. Now we dance as Solomon Islanders should, and proudly. Men and boys neither ogle nor jeer, but admire the beauty of antiquity. A woman can be a modern without rejecting her heritage, I have learned that.

Jully’s attentiveness melts to an impish grin. “I think you fear a bride’s jewels, Esme. Do they scare you?"

I look straight into Jully’s eyes. “Me, afraid? Ha!”

I strip off my modern T-shirt. Jully drapes the bandolier of shell monies over my head and shoulder, arranges it over my susus. I shed my cloth skirt and panties and city ways. Jully ties the maku string at my hips. We flit about like wild parrots, adding braided armlets, ankle bracelets, rows of tiny knee beads, giant bone earrings, a yellow and red Kwaio comb to my hair, all the time screeching for the joy of it.

< 4 >

Now I prance through the store, waggling my bare bottom. The blue maku apron covers only in front, and only a hand’s width. Jully thumps a beat on the shop’s largest slit-drum, and my strings of shell monies sing click-clack, clickity-clack.

She guides me into the window display. “Stand here, Miss Village Bride, so the sun may enhance your charms.”

“Ah, now I am lovely. You can present me for marriage.”

“Yes, I shall. But who will be the husband?”

“No matter,” I shrug. “A man is a man.”

She laughs. She knows I do not believe that.

She studies me, as if I were an ebony carving to be priced for sale. She says, “Yes, humm, good, but we lack something.” She studies me more. “Humm . . . ah, yes, oil!”

True, a bride must be oiled. “But this is a gallery, not the public market. We have no coconut oil.”

“I know it.” She stands, discouraged, then races to the counter and gets her bag. “Here, a jar of cold cream.”

“And colour me white? For shame! A proper bride glistens like obsidian, not a bland and milky coconut.”

“True.” She pauses, then digs under the counter, “I have it– Teak Oil! It makes our carvings gleam, and preserves them.”

< 5 >

I arch my back to point my susus. They stand tall, though draped in heavy shell monies. “I am well preserved now, sister.”

“In shape only; those old susus are dull as coconut shells.”

I swing at her, but she dodges, and again we are giggling children. Jully pours Teak Oil into her cupped hand and slathers me until I truly glisten. “Now, you are a model bride.”

“Oh, no, not yet! I lack the itch to submit my virginhead.”

“Aeii, Esme, you embarrass me.”

As usual, we chatter, laugh, tell lusty stories.

I am storying, a tale of the one-toed nasty man, when Jully motions with her eyebrows. A waetman tourist presses against the window. He hangs mid-stride, staring back at me as if like Lot’s wife, God struck him to stone. Whitemen go crazy for naked susus, I know that from the cinema. My susus are firm, not saggy like an old village woman. My nipples are prominent and dark as ebony. I readjust my bridal bandolier, and one susu bounds free. The waetman comes to life. He turns, and enters the shop.

“Good afternoon, Sir. May I help you?” Jully says. She is so polite, but laughter swells her breast, I feel it.

“Nah, I’m just looking.” He wanders the shop. He examines each carving, takes a spear and pretends himself a warrior, holds a shell necklace to the light. He is down each aisle, back again, working his way toward me, even yet in the window.

< 6 >

He gazes down at me – no, not gaze – leers! “My, this carving of a woman is remarkably life-like,” he says. He touches my arm and I shrink away. “Well, well, she isn’t a carving at all.”

“Sir, I am a bride-to-be.” My voice is cold ice.

His lips move, as if to engage a retort, but no sound comes. Finally, he says, “And a very beautiful bride-to-be!” He blurts it, like a shy boy with an unfamiliar burst of confidence.

“Actually, I am modeling an antique–a bride’s headband.”

He stares, but not at my headband. “You are an exquisite model!” he says. He wishes to say more, I feel it, but his face blushes red, as only waetmen can do. He looks away.

I ask, “You are from America, Sir?”

“Yes, Bellingham.”

I do not know Bellingham, but asking about America loosens his tongue. Soon, we are talking, Jully and I with him. He is doing a “shoot,” he is a photographer. He starts to tell more, but a white woman enters the shop, a New Zealander from the sound of her greeting, and Jully must attend her.

The American wants to photograph me. He says, “You’re incredibly beautiful, exactly what I’m looking for.”

< 7 >

“Oh, yes, I know that!” I say. He is like those young boys in secondary school, saying pretty things so I will favour them. But he is older than Father, my goodness, and white haired.

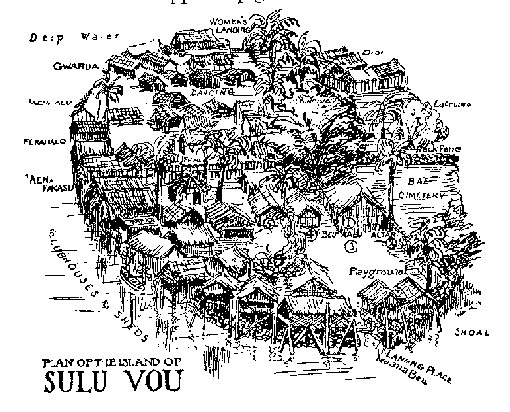

“No, I’m serious,” he says. “Strictly business. I’m doing a shoot on Sulufoa, the big artificial island off Malaita. I’ve studied their customs. You’re exactly what I have in mind.”

“Sulufoa?”

“Yes, have you been there?”

I only nod, but I wonder, Does he know it is my village?

More tourists enter. Jully’s shop overfloats with shoppers. A cruise ship must be docked at Point Cruz. Two approach us.

“Look, I’m keeping you from your work. May I explain this over dinner? I’m at the Mendana Hotel.” He gives me from his shirt pocket a small paper and says, “My card!”

That he knows of Sulufoa intrigues me. I will do it, even if Mendana Hotel is for waetmen. “Yes.”

“Tonight?”

“Yes, eight o’clock,” I say. My boldness surprises me.

< 8 >

He lumbers off, tall as a giraffe, arms swinging, footsteps heavy. Americans are so awkward–especially in dancing. Jully says it is so cold in America their hips freeze, that is why they are so graceless. I think so. This American is odd. At first he seemed a Peacecorps–shaggy hair, faded bluejeans, workman’s boots. But he wears a khaki soldier’s shirt with long sleeves. No Peacecorps would do that, they know the heat. Nor wear orange suspenders! That makes me laugh. Even though Peacecorps now sends olos, men with hair gray as his, this man seems something different. His card says, “Robert Kincaid, Writer-Photographer, National Geographic, Washington, DC,” also an address and phone.

I know National Geographic. So beautiful a magazine, and friend to the world. Photography is an art, I know that, and a photographer an artist. I will talk of Sulufoa with Kincaid, but I will not dance with him. I am graceful; he would embarrass me.

I am something late to Mendana Hotel, half-past eight.

The maitre d’ greets me, “Ho, Esme, why are you here?” He is a classmate from Teachers College.

“Oh, Tovua! An American waits me for dinner.”

Tovua’s eyebrows arch, but he smiles. “Well, it must be you, then. One guest told me, ‘When the most beautiful girl in Solomon Islands arrives, please show her to my table’”

< 9 >

“He said that?”

“Yes.”

“Aeii, he embarrasses me! But he does not know our customs. He is a photographer from America, and wishes to talk of Sulufoa. He had no other time to meet. Will you chaperon us?”

“But Esme, I am on duty.”

“No, not to eat with us, only to watch, and if any gossips are about, to verify that we only talked, and nothing more.”

“But Esme, that is not the same, you should–”

“Jully could not come, nor other friends.” Tovua is such a goody-two shoes, young, but mired in tradition. I touch his arm lightly, and ask him in our Lau language, “Please, Touva, this is important to Sulufoa, and to me.”

Tovua surrenders, “You know me, Esme. I will do it.”

Kincaid jumps up when Tovua presents me. He has consumed already three Fosters, the empty cans like hollow tattletales betraying his vice. The ashtray overfloats with cigarette butts. He says, “Well, Miss, you did come!” He traps my hand in his. He leans too close. He reeks of stale cigarettes and beer. I hate those stinks, both. I glide away, but greet him politely, tilting my head and saying, “Mr. Kincaid, good evening, Sir.” I slide into the corner booth, and Kincaid sits again. I scoot away so we are not touching. Tovua steps back. He is watching over us.

< 10 >

A waiter comes. I know him also, cousin of a friend. He brings water and a menu, and Kincaid asks, “Would you like a drink?” He means liquor, but I do not. Liquor is a sin to God.

We look the menus, and order dinner, and Kincaid says, “You know, I didn’t get your name.”

“I am Esme Soporo, a Lau of Malaita, but I do not have a card. I read that you are Mr. Robert Kincaid, an American.”

Kincaid grins. Something of him attracts me, though he is sweaty-faced, not handsome. He is rugged, like Clint Eastwood in the cinema. Or maybe it is his eyes, not only their blue colour, but some intrigue, some wisdom sharpened by years of travel. He says, “Call me Bob.” It makes me laugh, Bob, a blop like an escaped fart. I call him by his real name, Robert, as is proper.

Kincaid brims over with tales of so many places. He has been everywhere, even Africa and China. He displays a folder of his photographs: a tiny island in India emerging from the mist; Machu Picchu, a dead city, also Indian, but a different tribe; a bridge in Iowa. He shows many pictures of Iowa, corns growing, taller than kunai grass on Bloody Ridge, and wooden bridges with roofs and sides. “You speak as if Iowa were Heaven,” I tell him.

He laughs. “Yes, it is, I guess.”

Dinner comes. Mine is a small steak, filet mignon. Also rice. Kincaid has a stir fry, but without meat. Also potato.

< 11 >

He says, “Bon appétit!” He begins to eat.

I gaze at him. When he looks up, I whisper, “I cannot eat. I do not know how to use the eating utensils of the waetman.” Even though I know very well, I tell him that to test how well he understands our people. How will he treat me now?

He leans toward me and whispers, “Do what I do.” His lips brush my hair. He exaggerates his motions with knife and fork, but discreetly so other diners do not see. I mimic him as if I am a village girl, not of the city at all. Also I mimic that he holds his knife in his right hand, cuts, then transfers his fork from left to right, unlike we, who eat in the British style, more efficiently, with knife always in the right and fork to the left.

On purpose, I “accidentally” let fall a cut piece of steak.

“Don’t worry. It’s okay,” he mouths. “Try again.”

I fork another piece, and this time bring it correctly to my mouth. I smile, and he gives a wink of the eye.

“You are a good teacher, Mr. Robert Kincaid.”

He only shrugs. Yet, his eyes sparkle, the creases soften. Waetmen love to display their talents, and instruct others.

Dinner is a blessing, eating occupies us. When we finish, nothing camouflages our silence. He tries to make conversation: “Your gallery is interesting. How long have you worked there?”

< 12 >

I explain that Jully manages the shop. I go to visit.

He is silent. Then, “And what do you do? Student?”

He is surprised I am a graduate, but that news frees him to talk again. Educated men love to talk of education. And I also, I chatter on about my plans. “Probably I will study cultural anthropology. Maybe journalism or literature–I love to write. Or art–I paint, village scenes, facial sketches.”

He asks, “You have so many talents. Why anthropology?”

I had not thought why before, only that I wanted to. Now, it hits me: in anthropology my interests converge. We need an islands literature, not academic treatises. My art illustrates what words cannot convey. I tell him, “Solomons draw academics like moths to a lantern, many quite famous–but all whites, and all male. Melanesians should not be defined by Europeans . . . or Americans. I will write true stories of our people.”

Kincaid only gnaws at his knuckles, like a daydreamer, not speaking. At last he says, “That never occurred to me, but it’s true, isn’t it?” He leans toward me, “God, girl, you’re amazing!”

“No, not amazing; only becoming educated,” I say softly. It is best to be gracious. He is a visitor.

Kincaid knows to listen, he is attentive. He asks questions. With his own vignettes, he shades in the meaning of feelings I cannot express. He recites poetry, also lines from A Passage to India. He loves India, also Iowa.

< 13 >

I tell him of Lau. We are a special people. Stone by stone, my ancestors created living islands in the sea, without machines, without slaves. They drove no pilings, mixed no mortar, merely gathered stones and piled one onto another until a mound rose from the sea, then covered it with sand and earth hauled in their canoes. From their labour, villages grew.

“Sulufoa is the island of my mother,” I tell Kincaid. “I was born on that island, though now we live in Honiara.”

“No!” he says, as if to call me liar.

“I swear it, as God is my witness.”

Kincaid takes a long drink from his beer–his sixth. He searches my face, he tries to look inside me. “I knew it, somehow I knew it,” he whispers. “It’s destiny.”

I only smile. He is talking nonsense, or a wornout line.

Of Sulufoa, Kincaid has nothing but praise. Tomorrow, he will fly to Auki, hitchhike a truck to North Malaita, hire a canoe to Sulufoa. He will do a shoot, then his article.

< 14 >

“Your made-man islands are a wonder, amazing as the rice terraces in the Philippines,” Kincaid says. “But islands are things. Only remarkable people create monuments. My photographs will capture the strength and persistence and beauty of the Lau people. When I saw you in the window today, I knew you were the perfect model. Pose for me, Esme. I will make your face known to the world. Every time people hear the name Solomon Islands, your beauty will appear in their minds.”

< 15 >

I am beautiful, in face and form, and I have already seven boy friends, but only to stori with, and dance, not marriage. Women should date many men, not one, nor accept to be betrothed by their fathers as was the old custom. But beauty is a blessing of God, not of being Lau. Many Lau women are plain, and many from other islands are blessed equally as I. Thus, Kincaid honours me to represent Solomon Islands to the world.

Also, I do not tell him this: Mr. Cremmins gave Jully a small camera. She photographs me, and me, her. We sneak-look the magazines Mr. Cremmins and his wife buy from Australia and America, and paper the walls of our bedrooms with our own poses.

“Yes, I will do it,” I tell Kincaid.

He says, “Great! I’ll postpone my trip to Sulufoa,” and he becomes so talkative, full of plans, full of desires.

Next day I wear my favourite outfit to Mendana beach, so the world will meet a modern Solomon Islander: black and red Spandex bicycling pants (sent me by Mr. Cremmins’ daughter in Brisbane); a white tube top from Alice’s Boutique; my new Teva sandals. I wear also my Mickey Mouse wrist watch, and a gold necklace chain with a Mini Maglite, gifts from Peacecorps guys. I fluff my hair like a jungle fern, and top it with a spray of red hibiscus.

< 16 >

Kincaid waits me at the far end of the beach, beyond the great mango tree. Cameras hang from him like leeches. He waves, and starts toward me. He halts, throws both hands to his hips, like an angry father seeing his daughter come home late. I check Mickey. Ha, I am early, not yet half-four in the afternoon.

“My God, girl, what have you done?”

My mouth only opens. I have done nothing, I swear it.

“Your outfit! Where is the marriage costume?”

“Marriage costume?”

“From the store . . . headdress, necklaces, blue G-string.”

He makes me laugh. “You are silly. I am a modern woman.”

“No, don’t you see, that outfit was perfect, I–”

He stops mid-sentence, as if a crocodile snapped his voice from the air. “Of course, a modern woman. Yes, a modern woman who knows and appreciates the past.” He is playing with that camera, pointing it at me. “Contrasting photos, that’s perfect! I'll show you in both worlds.” He squiggles his pointer finger as if writing on air, “‘Spanning history, today’s Solomon Islands women step gracefully between present and past.’” I see no words, but Kincaid acts as if he has sketched a masterpiece.

< 17 >

He poses me, and so many pictures. “Walk toward me. Good, good! Swing your arms, lift your chin, turn to the side, other side, look here, look there, arch your back,” and all the time snapping photos, changing cameras. I sit on a rock, a log, in the sand. He stands, shooting down. He plops onto the sand, shoots up. I lean against the mango and cross my arms over my susus. I smile, pout, tease with my eyes. He puts more film. I throw my hands high, lock them behind my neck, stand with one hand on my hip, kneel in the surf, sit, splash water, stretch a leg, both legs, twist sideways and smile or say cheese and look away or imagine my boy friends or silly things. Kincaid darts around me like a coral trout, never resting, eyes alert, hands posing me, stepping back, stepping close, changing lenses, all the time talking, talking, talking. He talks even to his camera.

Shadows lengthen. Sunset passes. I did not see it.

“A few closeups and we’ll call it a day,” he says. He moves toward me, cameras clanking. With his hands, he positions my face, directs me, “Turn, turn . . . a bit more. I want to get your tattoos.” He says that, as if my Lau marks are a tourist site, like Sulufoa village or a half-sunken World War II ship. But I am Lau, proud of my lineage, and its mark–scar circle on each cheek, three scar lines toward the temple, two lines each to nose-bridge and jaw. I nod, yes.

< 18 >

Strong hands touch my cheeks, tender fingers trace my scars. He oozes desire. His hands slip to my shoulders, brush my susus, rest at my hips. Within me also, heat surges from my very soul, my heart is a pounding slit-drum. He has made this day special, I am indebted that he chose me as his model. That he is old, and I young, seems as nothing, nor that he is a waetman and I, black. Touch erases such differences. His lips press toward me. I am willing. I close my eyes and try to imagine he is Po’hoa, my boyfriend. I cannot; the stench of cigarette breath forbids me. Above the surf, a fruit bat squeals, coconut crabs scurry through the rip-rap. The spell is broken. I am body-to-body with a waetman on a public beach, about to kiss him. In Solomon Islands, every coconut has an eye, and each a dozen busy tongues. Kincaid is a photographer, seeking to create illusions. Beyond that, I do not know him, not as I know Po’hoa of Sulufoa. This Kincaid blazes into my life like a meteor in the night sky, but he offers only a moment of bliss, maybe a haunting memory, nothing of commitment. He will move on, to another India or Iowa, to another passion.

“No! We cannot!” I turn aside. I am a modern woman, but I know to control the sexual.

His kiss brushes my cheek. His eyes snap open. His hands engulf me again, draw my face toward him.

“No! I will not kiss you!” I push away.

< 19 >

His body sags. His eyes plead, but I am strong. His eyes narrow and he studies me. Again, he touches my scars. “Your tattoos–the design tells a story, doesn’t it?”

I nod. I explain the cutting. He winces. He whispers, “Was it terribly painful to be tattooed?” His voice falters.

I laugh, as if it were a nothing. I say, “Is it terribly painful to be circumcised as they do in America?”

He is silent, no more talk of tattoos. I do not tell him of marking my cousin-sister last year. We use a hardwood sapling, hone it beyond a razor. We rub black ash into the open wound. When scabs form, we carve the other cheek, with the same result. Her mind will teach her to block away that pain, as mine has.

Some families no longer apply tattoos, especially those who left Malaita to work on Guadalcanal. We form new customs here, mixing Malaita and Guadalcanal people with those of every island. When I marry and bear daughters, they will wear proudly the mark of Lau, but only in their hearts and minds.

Kincaid says, “I’m sorry, Esme. I got carried away.” He offers his hands, palms out, as if pushing me away, “Strictly business?”

“Can you do that, Sir?”

Our eyes meet, and he looks away, then back. “Yes!”

Kincaid backs away, begins shooting again. He circles like the shark. No talking now. Suddenly, he drops his camera to his side. “OK, we’ve got some keepers. But I still want you as a bride. Can you borrow that outfit? Early tomorrow?”

< 20 >

Posing is my dream, I love it. And lust no longer burns in his eyes, only work. “Yes, I will come. Jully will lend them to me.” But tomorrow, I will bring Jully. I do not tell him that.

He says, “You know, it’ll work out better this way. We reverse the stereotypes: modern girl in setting sun; traditional bride in dawn’s early light.”

Next morning, Jully and I are at Mendana before sunlight. Kincaid also. Jully dresses me. Kincaid shoots. He prowls the beach as yesterday, checking light, checking background, cameras clicking, go here, go there. But he poses me without touching. He snaps also photos of Jully, and we two together.

We finish close-up half-past seven. Kincaid rushes off to breakfast, then to Solair to arrange his flight to Malaita. He promises to come for us when he gets back, and tell us of his shoot in Sulufoa. I go with Jully to her shop.

The cruise ship has gone. Jully’s shop is empty. We stori. We are famous models now, but posing is only one something. We have boys and cinema and church to engage us. Mendana Avenue is Honiara’s main street. As people walk by, we imagine their thoughts by their stride and expression. Our mouths go dry from talking. “I am dying of thirst,” I gasp. I collapse in the agony of a Legionnaire lost on desert sands, and Jully dashes out for a Coca-Cola to rescue me from sure death.

Jully is gone too long. A customer enters and I must wait on him. He looks, but buys nothing.

< 21 >

Jully rushes back in, panting.

“Aeii, Esme, you are being gossiped! With that Kincaid!”

Her news pierces me like a volley of spears: alone with a waetman on Mendana beach. Kisses. Caresses. Intimate dinner. She slept with him, that Esme, she snuck from his room at dawn.

“Your Auntie says your brothers have heard the rumors. They are coming, you must hide,” Jully warns.

I have dishonoured Lau custom. They will thrash me for it. Girls have died from such beatings. Nor is there recourse: that I am gossiped is guilt enough. I hate it, this custom.

“I cannot. That is our tradition.”

“Yes, but a tradition outdated as slavery, or cannibalism. We are modern women, not chattel. Come, I must hide you!”

“Where? They know the island. I cannot hide.”

“I know a place. Come!”

Jully locks the shop, sneaks me into the alley, into Mr. Cremmins’ Land Rover. “It is OK. I drive it to pick up art works,” she says. She hides me; I am a copra sack on the floor.

< 22 >

Jully drives past the airport, past the villages, takes a sandy trail into the forest of the palm oil plantation. The road ends. Jully searches, finds a shrouded path. We hike, and come to a palm-leaf house, isolated as a leper’s hut. “You will be safe here. The father is a carver; his wife my cousin-sister,” Jully says. “I will find a way to dissuade your brothers.”

Comes the next night. Jully brings news: gossip ferments; my brothers rant, as well Father. Kincaid remains in Honiara–my friends at Solair have sold out every flight; all inter-island boats to Malaita are full. Sulufoa is off-limits. Nor can he leave Solomons. His passport has walked away from his room.

“An embassy friend of Mr. Cremmins will help,” Jully says. “He will negotiate between your father and the American.”

I can only wait, and have faith in Jully. I help the family in their gardens, and haul wood. I am their instant daughter.

Another day passes.

Comes morning. Jully hails our hut from the trail. I go outside. Father stands beside her, and with an angry pose.

“Did you sleep with the waetman, Daughter?”

“No, Father. I met him only to pose for photographs.”

“Did you do anything to dishonour yourself, or us?”

“No, Father, nothing. Only posing.”

< 23 >

“Before God you swear it?”

“Yes, Father, especially to God.”

He nods. “Yes, this is as Jully tells me. And the waetman also. He paid a proper compensation. You may come home.”

Kincaid is nothing to me now, another passing waetman, a photographer, tourist, contract worker, Peacecorps. They sniff at the boundaries of our world, do their business or foolishness, disappear. Kincaid went to Sulufoa. I never saw him again.

From the negotiation, Kincaid paid my family 250 dollars American and two small pigs to quiet the gossip. Jully demanded he compensate me with a camera, for his cameras were the root of these problems. Kincaid objected, but Chief Gwali Asi of Sulufoa said it must be done, or Kincaid would never see Sulufoa. I have that camera with me, this Hasselblad of Kincaid’s, and film also.

Compensation closed the matter. Any who gossip now of Kincaid and me violate custom law. They would pay dearly at the fists of my brothers, who remain eager to protect their sister’s honour.

Two years pass. A package comes from America: National Geographic, five copies. As well, a dozen photographs of me at Mendana beach, modern girl and traditional, and two of Jully. He was true to his word, that Kincaid.

< 24 >

As for the magazine, I, Esme, am the cover, innocent bride, “Girl of Malaita’s Artificial Islands.” Inside displays Sulufoa to the world–our island at dawn, fishermen, grandmother’s leaf house, the church, an uncle in his canoe, hauling coral rock. Also a small photo of Jully and me, arm-in-arm in modern dress, and Chief Gwali Asi in ceremonial necklace and chief’s medallion.

I take my package to Guadalcanal Arts at closing. Jully and I study each photo. Tiny memories flicker from the background of Kincaid’s houses and faces and sceneries.

“There, behind that tree, Po’hoa first kissed me,” I say.

“And what more, what more?” Jully begs. I only wink.

Jully thumbs Kincaid’s magazine. There are other peoples also, peoples of Indonesia and Canada. Whooping Cranes. A dirty river. A circus troupe in America, with a hunchback midget.

Jully points out a tiny picture at the back of the magazine. “Look, it is that photographer!” It is Kincaid, cameras still hanging like leeches, but also with a necklace of porpoise teeth. Jully brings Mr. Cremmins’ reading glass. Kincaid wears also his silver medallion, but on the Sulufoa necklace, not its chain. It is pure silver, from Spain, he said, inscribed Francesca. We saw it the morning Jully and I posed for him. It fell from his shirt when he bent to take a photograph. I challenged him, “You are married, Mr. Kincaid?” He blushed. “No, not married. Not with a legal document. Francesca is my soul-mate. I wear her name over my heart so she will always be with me.” He looked away, he could not face me, and whispered, “Forgive me, Esme. I am a weak man." I only shrugged, for I was angry, and hurt. I thank God for my resolve. Love is a sacred gift, not a plaything.

< 25 >

Jully and I spread Kincaid’s photos on the counter. They are big ones, each larger than a page in National Geographic. We study each carefully, as Jully would inspect a carver’s work.

“They show us to be modern women, eh?” Jully says.

I think so, but I feel an emptiness. I only nod.

We pick them up, each one. We turn them, study them.

“We pose as they do, Esme . . .” Her thought trails off.

I am wondering also. Disappointment claws within me.

Suddenly, Jully shrieks. She dashes to the back room, to Mr. Cremmins’ office. Drawers open and bang shut. She sails back into the show room, clutching an armload of magazines like squirming babies. She spreads them on the counter, opens them to the foldout pages. “Look, it is how they wear their clothes that makes them modern girls, not only the pose.”

“Yes, I see it.”

We race out together, to Jully’s house and mine. We go beyond Mendana beach, beyond the mangroves. No one comes here.

Jully strips off her working clothes. I anoint her with oil. She drapes herself in a length of bright cloth, its mesh open as mosquito netting. She poses in halter top, unbuttoned blouse, bikini suit, in off-shoulder dress, in lava-lava slung low at her hips. I am busy as Kincaid with my Hasselblad, posing her, circling, shooting, checking background, checking light.

< 26 >

Jully glistens in the setting sun. Lengthening shadows enhance her dark beauty, she is more alluring than the pale girls in those magazines. Jully does not pose as girls in Penthouse, nor will I. They are nasty poses, nasty girls.

“OK, we’ve got it,” I shout. I drop the camera to my side. “You are perfect, Miss Jully.”

Now, I become the graceful porpoise, leaping, twisting, posing my woman’s curves to my friend’s discriminating eye.

America will soon know the modern Solomon Islands woman, for we soon shall be featured in Vogue and Mademoiselle.

Note: The editor of Living on the Edge asked each author to write a short commentary on how he/she came to write the story, and included each in the book. Mine follows.

When I returned to the Solomons in 1991, I was struck by how aggressive and “less traditional” many young Solomon Islands women had become since my Solomons stay in the late 1970s. I wrote a long essay, started a novel, tried to figure out how best to present these “new” Solomons.

Then, I read Bridges of Madison County, and marveled at its enormous success (sales, readers): a modern colonial romance where the white man sails in, not to an island paradise, but to Iowa, finds a willing native gal (who, in Iowa, is married and an Italian import), has a delicious romp, then sails off. Best of all, said romp satisfies the native gal for life. Some stud!

So I put Waller’s hero in the Solomons, and introduced him to the thoroughly modern Esme. “American Model” resulted.

Esme still puzzles me–I can’t understand why she doesn’t always “act like a Solomon Islander,” but I know that deep down, traditional values still guide her. She, like Francesca in Bridges, might succumb to the charms of a visiting prince–certainly many Solomon Islands women do–but I doubt it. Intercultural relations are more complicated than they seem on the surface.

|